Water Crisis in Lima: A Tale of Two Worlds and Inequity

In Lima, Peru, over 635,000 residents lack access to running water, primarily relying on infrequent deliveries from tanker trucks. Conditions are harsh, with many families receiving only 30 liters of water per day, significantly below the recommended minimum. The disparity is showcased by the stark divide between affluent neighborhoods and the impoverished outskirts burdened by inadequate access and poor infrastructure, exacerbated by climate change and urban planning failures.

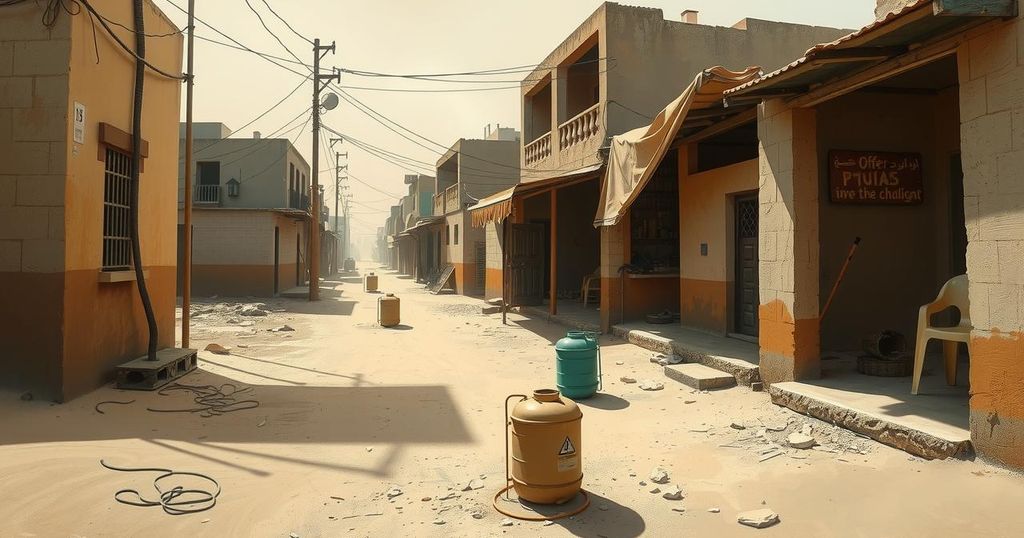

In the arid hills surrounding Lima, the capital of Peru, an estimated 635,000 residents dream of having access to running water, relying instead on water delivered by tanker trucks. Lima, which houses over 10 million people, is the second largest desert city globally, with scarce rainfall despite its proximity to the Pacific Ocean, the Andes, and several rivers. Many of those without adequate water live in informal settlements located high above the city, where municipal water and sewer lines are inaccessible.

Water delivery occurs weekly in areas like San Juan de Miraflores, where blue tanker trucks distribute water into large drums. However, these drums often lack hygienic standards. Catalina Naupa, a local resident, noted, “We get stomach cramps and migraines. There are worms in the bottom of the tank.” During winter, muddy conditions on the streets can prevent water truck access altogether, forcing families to stretch their water supply for laundry.

Residents receive an allocation of approximately 30 liters (eight gallons) of water per person daily, significantly below the United Nations-recommended minimum of 50-100 liters. The city’s water utility, Sedapal, expresses concern about potential water rationing as the rainy season approaches and hopes for refilled reservoirs.

Climate change poses further challenges to water availability, impacting mountain water levels and river flow. Antonio Ioris, a geography professor, cautioned that inadequate urban planning and the lack of prioritization of poor populations’ needs perpetuate this crisis. Migrants from rural areas fleeing economic hardship compound demand for city water resources.

In certain sections of San Juan de Miraflores, access to water is compromised by steep terrains where trucks cannot reach. Consequently, residents often pay exorbitant prices—reportedly six times more than utility-connected households. A particularly striking divide is illustrated by the wall dubbed the “wall of shame,” which physically segregates affluent neighborhoods, such as Santiago de Surco, from poorer areas. Residents of Surco enjoy a high consumption rate of 200 liters per day.

Contrastingly, Kristel Mejia, who operates a soup kitchen in the impoverished sector, remarked upon the stark differences, stating, “Surco seems like another world.” This disparity highlights the ongoing struggles faced by the underprivileged in securing basic necessities such as water in Lima’s outskirts.

The dire conditions surrounding access to clean water in Lima, Peru, expose significant societal inequalities as many residents in poorer neighborhoods rely on infrequent and inadequate water deliveries. The challenges posed by both climate change and poor urban planning necessitate urgent attention to ensure equitable access to vital resources. The divide symbolized by the physical barriers separating wealth and poverty in Lima encapsulates the broader issues of migration, public policy priorities, and infrastructure neglect. Addressing these issues is imperative for improving living conditions and ensuring that all citizens have access to the essential resource of clean water.

Original Source: www.france24.com