Community Seed Banks in Zimbabwe: Resilience Building Amid Drought Challenges

Mudzi district in Zimbabwe faces severe drought challenges, exacerbated by climate change. Community seed banks like Chimukoko provide free access to drought-resistant seeds, allowing farmers to adapt to harsh conditions. More than just seed storage, these banks empower local communities and promote agricultural biodiversity. The push for formal recognition and support from the government could further enhance their effectiveness.

In Zimbabwe, community seed banks are becoming vital resources for farmers battling the challenges imposed by climate change and erratic weather patterns. One particularly notable location is the Mudzi district, where the drought that struck last August severely affected local crops, including key staples like corn. This disaster follows a trend, as the El Niño weather phenomenon, aggravated by climate change, has left millions across Southern Africa hungry, with nearly half of Zimbabwe’s population affected.

To cope, residents of Mudzi have turned to Chimukoko, a community seed bank established in 2017. This facility allows farmers to access drought-resistant seed varieties such as sorghum, millet, and peanuts for free, bolstering their chances of successful harvests. The community’s reliance on these hardy local varieties is partly due to the need for agricultural resilience against the forecasted potential 60% decrease in crop yields in the coming decades, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

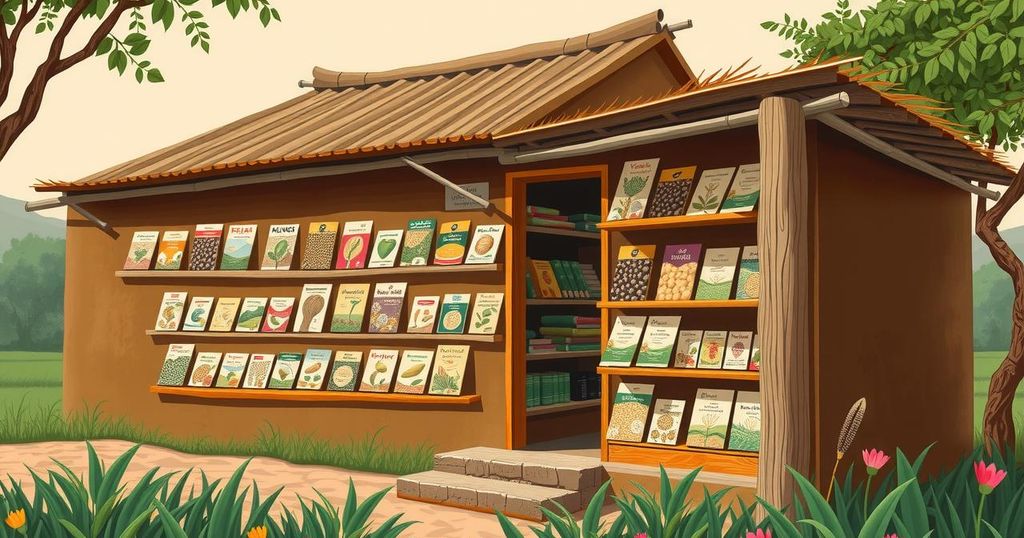

Seed banks have traditionally been large, centralized operations, but in places like Zimbabwe, they are swinging towards smaller, grassroots initiatives. The Chimukoko seed bank, for example, conserves 20 types of seeds, allowing local farmers to implement traditional farming methods that had fallen out of favor due to industrial agriculture influences. Andrew Mushita, an agronomist, emphasized the importance of these seed banks, stating, “We see community seed banks as centers of agricultural biodiversity.”

Ownership of local crops helps communities develop resilience to climatic stresses. Farmers in the Mudzi district were able to directly access seeds when their own crops failed, which allowed them to replant for the next growing season, overcoming considerable adversity. Unlike the commercial dependence on monocropping, community seed banks encourage farmers to explore multiple crops, mitigating risks inherent in climate change.

However, community seed banks faced opposition early on from formal conservation entities that believed such initiatives should be reserved for trained experts. Ronnie Vernooy of the Alliance of Biodiversity International noted an evolution in attitude, with increasing recognition of the merits of community-led efforts. Such banks have since gained traction globally, promoting local control over agricultural practices.

The concept initially took root after the catastrophic famine in Ethiopia during the 1980s, although in Zimbabwe, the journey has been slow. The first seed bank, created in Uzumba-Maramba-Pfungwe in 1999, experienced skepticism from locals, but educational outreach and an increase in farmers’ understanding helped shift perceptions over time. With burgeoning interest, CTDT has established 26 more seed banks across Zimbabwe, enhancing the diversity in crop selection.

Constructing seed banks involves local community engagement. While CTDT offers comprehensive support, residents decide if and how to build a seed bank, ensuring a communal commitment which is vital for sustainability. Each seed bank typically costs around $30,000 and operates on a loan-based system, returning more seeds after harvest.

As more farmers participate, these community efforts are aiding the governmental push for a national seed policy that would formalize such initiatives. Vangelis Haritatos, the Zimbabwean deputy minister for agriculture, recognized the essential role of smallholder farmers in conserving plant genetic materials during a workshop in Harare last November.

There are, however, hurdles to navigate. The legal framework surrounding these community banks is still developing. Mushita suggested that establishing a national policy is critical to making these seed banks formal entities nationwide. Early indicators show promise; the variety of crops being grown has increased significantly due to these efforts, and while conclusive data is still emerging, anecdotal evidence points to greater agricultural resilience in communities with seed banks.

Successful outcomes from other countries further bolster this assessment. For instance, a recent study in Malawi revealed that community seed banks improved food security and farming resilience. While community-led facilities like those in Mudzi operate simply, partnerships with larger institutions like ICRISAT facilitate advanced breeding of robust crop varieties, enhancing long-term food security in Zimbabwe.

In conclusion, community seed banks represent a promising strategy for Zimbabwean farmers navigating the complexities of climate change. With continued support and development, these initiatives could not only transform local agricultural practices but also contribute to broader efforts to ensure food security amidst climbing global temperatures.

Overall, community seed banks in Zimbabwe are emerging as essential resources for farmers combating the impacts of drought and climate change. Initiatives like the Chimukoko seed bank exemplify how local engagement can foster agricultural resilience. As the push for supporting these banks grows, they appear poised to play a significant role in enhancing Zimbabwe’s food security and agricultural diversity for the future.

Original Source: www.newzimbabwe.com